I've been teaching a course on religion in ancient Egypt since 2000, and I've always wanted to incorporate experiential or embodied learning. My training is in Religious Studies, where such pedagogy is no easy thing. I'm not about to ask Buddhist students to participate in the Eucharist. Even in Classics, where I am now, sacrificing a bull or reading entrails in my classroom is beyond consideration.

Inspired by Jentery Sayers' work in physical computing and "prototyping the past," I realized that embodied pedagogy need not mean becoming the people we study. Prototyping could function as a form of pedagogy about the ancient world.

I needed something low tech and portable, easy to incorporate into a classroom without requiring hours of technical training. I needed something where the making was the learning. So I turned to Legos.

Beginning in 2016 in my Religion of the Pharaohs class at the University of the Pacific, I dedicated the day we studied about major New Kingdom temples (especially the ones in ancient Thebes known as the Karnak Temple and the Luxor Temple) to physical prototyping with Legos. We built ancient Egyptian temples with Legos.

For preparation, students read chapters 3 & 4 (about temples and festivals) in Emily Teeter's book Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. I lectured very briefly on the structure of New Kingdom temples and the ways they replicated the moment of creation: the vegetative columns, the east-west axis following the course of the sun, etc. Even the floor rises slightly as one progresses through, imitating the emergence of the benben stone—the primordial mound that rose from the watery abyss of Nun at the moment Atum created the world. We also viewed and discussed video reconstructions from the UCLA Digital Karnak project about the temples two major festivals connected to those temples (the Opet Festival and the Beautiful Feast of the Valley).

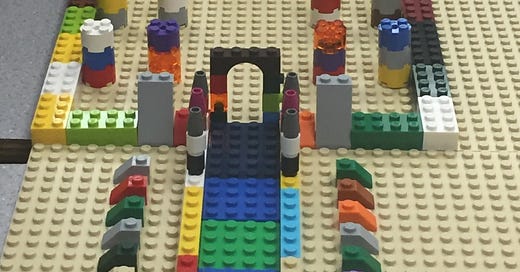

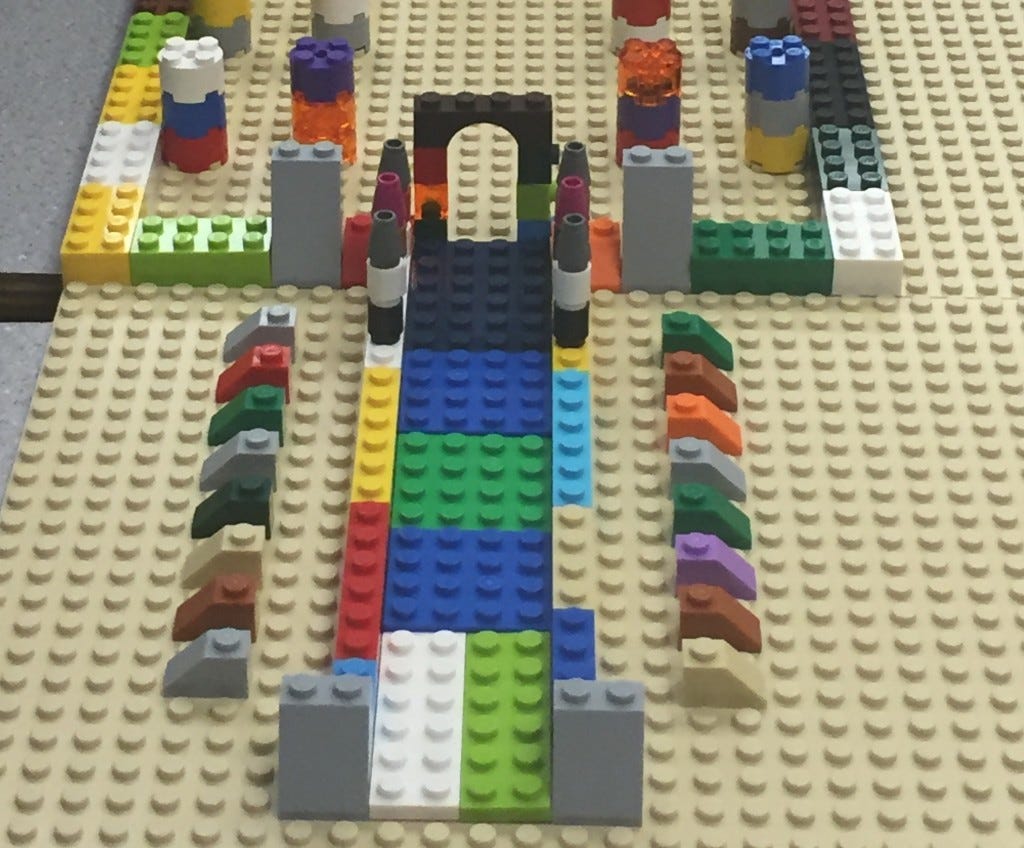

Then I brought out the Legos, divided students into small groups, and instructed them to create a temple or components of an ancient Egyptian temple. All the temples ended up slightly different.

I initially worried the activity would be frivolous. Legos are "toys." Buiding with Legos is "play" not "work."

I couldn't have been more wrong. As I wandered the room, I heard students discussing the shapes of the pylons, the best way to use their bricks to create obelisks, where to place the sacred lake, and how to make their hypostyle halls resemble papyrus and lotus reeds.

How do you create a street lined with rams-headed sphinxes when all you have are little plastic pieces? One group used the small, asymmetrical quadrilaterals.

While another used round pieces topped with eyes.

Some groups focused on the sanctuary. One group attempted to create a sphinx-shaped sphinx.

When the giggling commenced, after a declaration that the sphinx was "cute", I pressed them: why make a "cute" sphinx? Would ancient Egyptians have thought their sphinxes "cute"? They reassessed what they were doing. One group really focused on the barque shrines for the divine statues.

While another on creating a hypostyle hall and sanctuary.

I repeated the the activity the next time I offered the class and plan to do so in the future, because I am convinced that my students will remember ancient Egyptian temple features and ritual purposes of those features better than if we had simply discussed the readings. One student told me she thought you really had to know what a temple was like to be able to reconstruct it.

We historians of the ancient world sometimes get caught up in the primacy of historical accuracy. Legos can never accurately represent a historical site. Students had to negotiate between the their vision of a temple (based on site plans in their books, photographs of the reconstructed ruins, 3d renderings on Digital Karnak) and the practicalities of the little plastic bricks. The limits of Lego forced them to think about which features they wanted to emphasize, and which they were willing to let go.

And thus, the learning was in the making, in the process.